DevOps Certification Training Course

- 139k Enrolled Learners

- Weekend/Weekday

- Live Class

With the boom of DevOps technology, it becomes inevitable for any IT person to work on multiple data simultaneously and your data is ever-evolving with time. It is also essential to track every change in the data and be prepared to undo or revert any undesired change when required.

I must confess, versioning my data in Git allow me to be more experimental in my project development. If I mess up, I know git always has a way to undo and/or revert that version of my project to the way it was before I screwed up. Each Git workflow layer is designed to allow the data changes to be reviewed and modified and/or corrected before moving the data in the next stage. So the following are the mistakes that are covered in this blog:

Un-stage files/directories from Index

While adding and/or modifying files you often tend to use the default behavior of ‘git add’ command, which is to add all files and directories to the Index. Many a time you feel the need to un-stage certain files or modify them one last time before committing them.

Syntax: git reset <filename/dirname>

Un-staging files from the Index area gives you another chance to re-work on your data before committing to a local repo.

Edit the last committed message

Command: git commit --amend

You can edit the latest commit message without creating a new one. To list the commit logs, I have set an alias ‘hist’:

Command: git config --global alias.hist 'log --pretty=format:"%C(yellow)%h%Creset %ad | %C(green)%s%Creset%C(red)%d%Creset %C(blue)[%an]" --graph --decorate --date=short'x

Do not amend the commit message which is already pushed on to a remote repository and shared with others, as that would make the earlier commit history invalid and thus any work based on that may be affected.

Forgot some changes in the last commit

Let’s say you forgot to make some modifications and already committed your snapshot, also you do not want to make another commit to highlight your mistake.

Command: git commit --amend

I have highlighted how the recent commit object’s sha-1 id has been recreated and changed. I pretended to have made a single commit blending both the changes into one.

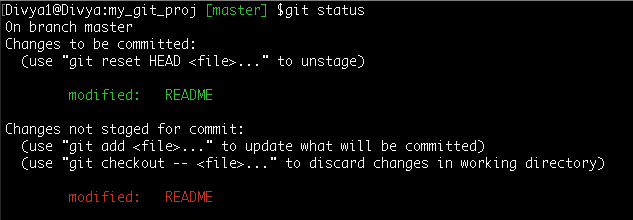

So, here is a case where I modified the ‘README’ file and staged it. Next, I modified the same file a second time but realized that I didn’t want the second change.

Now, let me not undo the entire change manually, I can simply pull the staged version of the file.

Syntax:

git checkout -- <filename> –local changes in a file

git checkout -- <dirname> –local changes in all the files in the directory

Command: git checkout -- README

So, I discarded my last changes to the file and accepted the staged version of the file. In the next commit, just the staged version of the file goes in the local repository.

I want to remove certain data from the local repository but keep the files in the working directory.

Syntax:

git reset --mixed HEAD~

git reset --mixed <commit-id>

Command: git reset --mixed HEAD~1

HEAD~1 indicates a commit just before the recent commit pointed by the current branch HEAD.

Files in the current snapshot removed from both the local repository and the staging area. Add the following patterns in the global .gitignore file to exclude them from being tracked by git.

vim ~/.gitignore_global

# password files #

*.pass

*.key

*.passwd

With this, the commit that had the snapshot of password files is removed, and you get a clean staging area. My files are still present on my working directory but no longer present in the local repository, also will not be pushed on a remote repository.

Caution: If you lose them git cannot recover them for you as it does not know about it.

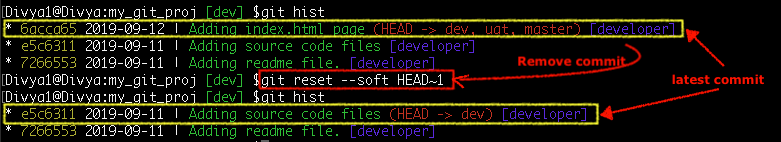

Syntax: git reset --soft [ <commit-id>/HEAD~n>]

The ‘–soft’ option just remove the committed files from the local repository while they are still staged in the Index and you can re-commit them after a review. <commit-id> is the sha-1 of the snapshot that you want to remove from the local repo. <HEAD~n> where n is the number of commits before the HEAD commit

Command: git reset --soft HEAD~1

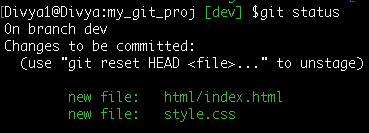

Modify files and stage them again

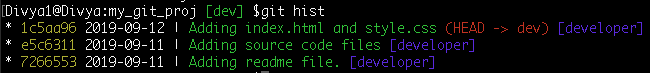

Command: git commit -m 'Adding index.html and style.css'

Your commit history now turns out to be:

Syntax:

git reset --hard HEAD~n –reset the project to ‘n’ commits before the latest committed snapshot

git reset --hard <commit-id> –reset the project to given commit id snapshot

Command: git reset --hard HEAD~1

The latest commit and the corrupt files are removed from the local repository, staging area as well as the working directory.

Caution: It’s a dangerous command as you end up losing files in the working directory. Not recommended on a remotely shared repository.

You can ump to an older state of your project in the history of time. If you mess up in the latest version or need enhancements in older code, you may want to create another branch out of that old project snapshot to not hinder with your current work. Let’s see how:

a. List out the project history and decide on the older commit id, command: git histb. Create another branch out of the commit id:

git checkout -b old-state e7aa9a5

c. Continue working on the code and later merge/rebase with the ‘master’ branch.

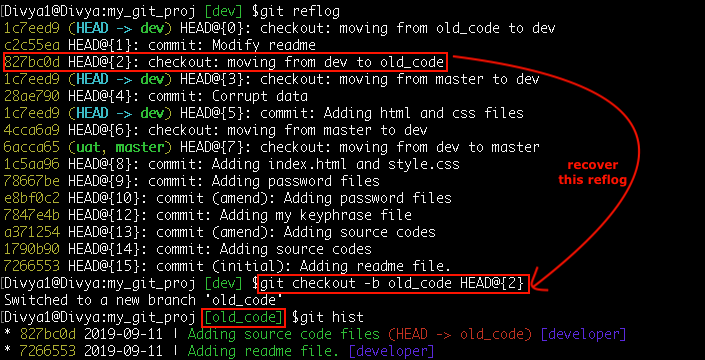

It is possible to regenerate the lost work on a reference branch. Say, I deleted the branch ‘old_code’ without merging with the main branch and lost the work. And no, I did not push the branch to a remote repository either, what then? Well git tracks and keep a journal entry of all the changes done on each reference, let’s see mine: git reflog

So, HEAD@{2} is the pointer when I moved to ‘old_code’ branch, let’s recover that:

Syntax: git checkout -b <branch-name> <commit-id>

Command: git checkout -b old_code HEAD@{2}

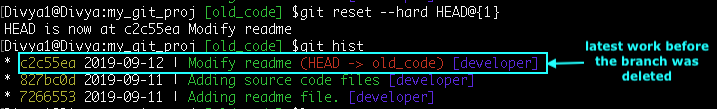

You must be now in the ‘old_code’ branch with your latest work at the time of its creation.Additionally, the ‘reflog’ pointer at HEAD@{1} was the recent commit made on the ‘old_code’ branch.To restore this unique commit just run the command as: git reset --hard HEAD@{1}.This also restores the modified files in the working directory.

If you would want to know in detail how this command works and how can you manage the ‘reflog’ entries, you may as well read my earlier post on recovering the deleted branch from git reflog.

git revert is used to record some new commits to reverse the effect of some earlier commits.

Syntax: git revert <commit-id>

From my commits logs, I would like to reverse the change done in the highlighted commit id:

Command: git revert 827bc0d

It is better, that you do not reset ‘–hard’ the shared commits, but instead ‘git revert’ them to preserve the history so that it becomes easier for all to track down the history logs to find out what was reverted, by whom and why?

You can use the same logic of referring the commits concerning the HEAD pointer instead of giving the commit id, as in HEAD~3 or HEAD~4 and so on.

You can rename a local branch name. It so happens many times that you may wish to rename your branch based on the issue you are working on without going through the pain of migrating all your work from one location to another. For instance, you could either be on the same branch or a different branch and still be able to rename the desired branch as shown below:

Syntax: git branch -m <old_name> <new_name>

Command: git branch -m old_code old_#4920

![]()

As you may wonder does git keeps of a track of this rename? Yes, it does refer to your ‘reflog’ entries, here is mine:

Renaming a branch will not affect its remote-tracking branch. We shall see in the remote section how to replace a branch on the remote repository

How I wish I would have made certain commits earlier than others and would have not made some commits at all. Interactively re-arrange and edit the old commits to effectively fix-up or enhance the code

Syntax: git rebase -i <after-this-commit_id>

Command: git rebase -i fb0a90e –start rebasing the commits that were made after the commit-id fb0a90e

Re-visit the git rebase documentation to understand how is an ‘–interactive or -i’ rebase different from a regular rebase.

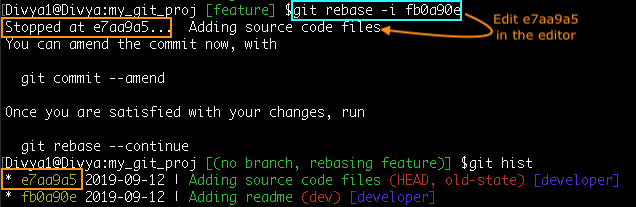

In this case, you need split an old buried commit into multiple logical commits.

Syntax: git rebase -i <after-this-commit_id>

Command: git rebase -i fb0a90e

In the rebase editor, you must choose e7aa9a5 commit id and change it to ‘edit’ instead of ‘pick’.

You would now be in the project’s version of commit id-e7aa9a5. First, reset the commit history and staging area to the previous commit-Command: git reset HEAD~1

Second, edit + stage + commit the files individually

Commands:

git add code && git commit -m 'Adding initial codes'

git add newcode && git commit -m 'Adding new code'

Third, continue the rebase and end.

Command: git rebase --continue

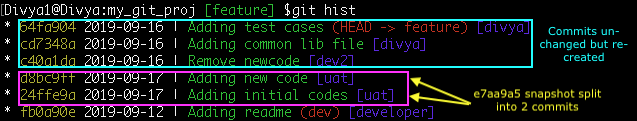

Fourth, view the history with additional commits.

Command: git hist

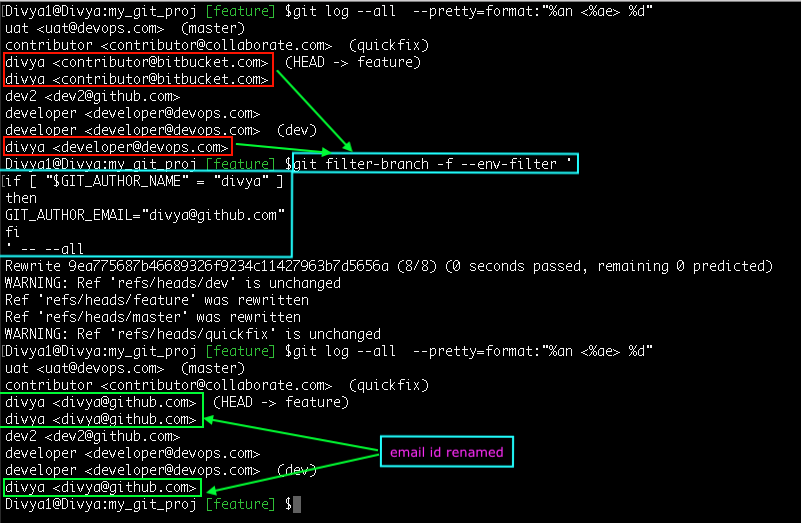

Change author-email in all commits on all branches

I have been versioning and committing my project files in git since a long time now, but until now it never struck me that my email id was compromised in my commit history logs which are even published on remote repositories. Well, this may happen to anyone when you initially set up the configurations in the “.gitconfig” file.To my relief git can re-write the environment variables we provide when creating a commit object.

First I get the list of email ids to decide the ones I want to change:

Command: git log --all --pretty=format:"%an <%ae> %d" –This prints author-name<email-id> (refname/branch-name)

Second, I run through every commit on each branch and re-write the commit object with the new email id

Command:

git filter-branch --env-filter '

if [ "$GIT_AUTHOR_NAME" = "divya" ]

then

GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL = "[email protected]"

fi

' -- --all

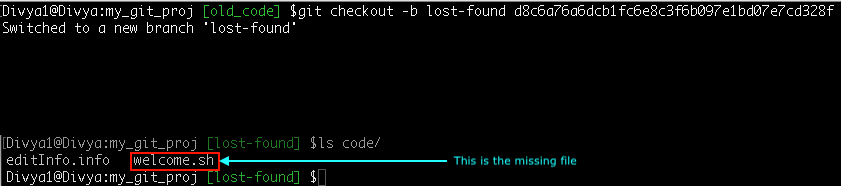

Lost and found files

Suppose you have lost a certain file and you do not remember its name, but could recall certain words in the file. In this case, you can follow these steps-

Step 1: List all the commits that ever contained the file snapshot with the searched pattern

Command: git rev-list --all | xargs git grep -i 'timestamp'

Step 2: Create a new branch ‘lost-found’ from this highlighted commit-id

Syntax: git checkout -b lost-found d8c6a76a6dcb1fc6e8c3f6b097e1bd07e7cd328f

Forgot which branch has my commit-id

At times, after you detect a buggy commit id you might as well want to know all the branches that have this commit on them so you could fix them all. Checking out each branch’s history is not very practical in a large multi-branch project.

A bad commit made in my navigation building application once broke the code, that’s when I used the ‘git bisect’ command to detect the commit id that was bad followed by the command: git branch --contains <commit-id> to list the branches with that bad commit.

So, now I know all the branches that still have the bad commit, I could either revert or reset this changeset.

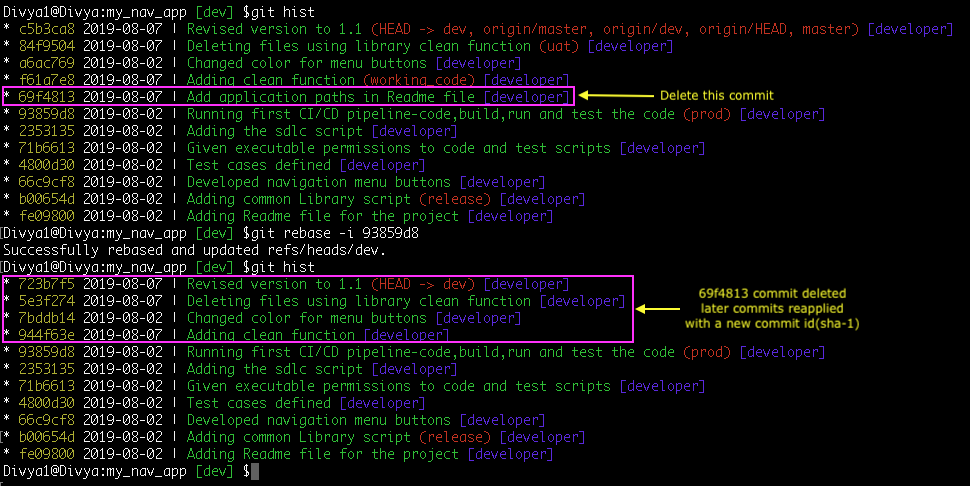

Delete a commit from history

Sometimes I feel the need to just wipe out a commit from the history and leave no trail of it. I would not recommend you to try this stunt on a shared branch but only on your local branch.

Syntax: git rebase -i <commit-id>

Command: git rebase -i 93859d8

In the rebase editor-> replace ‘edit’ with ‘drop’ for the highlighted commit id: 69f4813

In some of the cases, this re-writing may result in conflicts. You must resolve conflicts then proceed further.

Warning: This is a dangerous command as this re-writes history and may lose data.Such a branch differs from its remote-counterpart and will have to be pushed with the --force or --force-with-lease option.

Pushed a wrong branch to the remote

Now, here is what I want to do- I want to delete a remote branch and also stop tracking it from my local branch.’git push‘ command when used with the --delete option deletes the remote branch So, this is how I get the local copy of the cloned project –

git clone https://github.com/greets/myProj.git

cd myProj

Once, the remote branch is deleted others on the shared repo must refresh and update their remote references with the --prune option to delete the missing object references: git fetch --prune -v origin

In this post, I have mentioned some of the common mistakes or changes that git can help you fix. Every code is unique and developed in its way, so there are also different ways of approaching and fixing a problem. You could always refer to the official git documentation to understand how various git commands safeguard your source code and how to utilize the commands the best way possible.

Now that you have understood the common Git mistakes, check out this DevOps training by Edureka, a trusted online learning company with a network of more than 250,000 satisfied learners spread across the globe. The Edureka DevOps Certification Training course helps learners to understand what is DevOps and gain expertise in various DevOps processes and tools such as Puppet, Jenkins, Nagios, Ansible, Chef, Saltstack and GIT for automating multiple steps in SDLC.

Got a question for us? Please mention it in the comments section of this “common Git mistakes” and we will get back to you

| Course Name | Date | |

|---|---|---|

| DevOps Certification Training Course | Class Starts on 21st January,2023 21st January SAT&SUN (Weekend Batch) | View Details |

| DevOps Certification Training Course | Class Starts on 30th January,2023 30th January MON-FRI (Weekday Batch) | View Details |

| DevOps Certification Training Course | Class Starts on 20th February,2023 20th February MON-FRI (Weekday Batch) | View Details |

REGISTER FOR FREE WEBINAR

REGISTER FOR FREE WEBINAR  Thank you for registering Join Edureka Meetup community for 100+ Free Webinars each month JOIN MEETUP GROUP

Thank you for registering Join Edureka Meetup community for 100+ Free Webinars each month JOIN MEETUP GROUP

edureka.co